I’ve been asking many students that question lately.

This semester I am a visiting instructor of physics at Indiana University Purdue University in Fort Wayne (IPFW). I love physics and teaching it is loaded with fundamental challenges in cognitive design. In many ways, the physics classroom is a cognitive design laboratory. I’m hopeful the lessons I learn there will transfer to my consulting efforts in the workplace.

This semester I am a visiting instructor of physics at Indiana University Purdue University in Fort Wayne (IPFW). I love physics and teaching it is loaded with fundamental challenges in cognitive design. In many ways, the physics classroom is a cognitive design laboratory. I’m hopeful the lessons I learn there will transfer to my consulting efforts in the workplace.

One of the challenges involved in helping others learn physics is correcting deeply held misconceptions about how the world works. From seemingly simple ideas about position, velocity, force and acceleration to more basic assumptions about the nature of space and time, our common sense is loaded with conceptual mistakes. We have the same challenges in the workplace only they have to do with how employees think about innovation, customers, quality and other basic notion that drives performance.

So I am always on the lookout for new scientific research into the memory of deeply held but false beliefs. For example, Duke University just published some interesting research on the hypercorrection effect. They found student’s confidence in their answer plays a big role in how they correct misunderstandings. The higher the confidence the more readily the student makes a correction but without reinforcement the effect lasts about a week. More specifically:

“Although high-confidence errors may be easily corrected in the short-run, our findings suggest that one presentation of feedback is not enough to produce a long-lasting correction of deeply entrenched false knowledge,” Butler said. “Without further practice, high-confidence errors seem to be more likely to return over time.”

This means that some deeply held beliefs might not really be that hard to change, at least initially. From a teaching standpoint there is a premium on knowing which errors occur with high confidence. Such topics require additional work even if the initial error appears to be corrected.

How can we collect and use confidence-in-response information in the evaluation and learning process?

Image: Mark Master’s Laser Lab at IPFW.

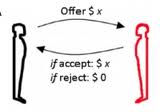

When selecting among alternatives, the order in which the choices are presented and the speed at which the decision is made, strongly shape the outcome.

When selecting among alternatives, the order in which the choices are presented and the speed at which the decision is made, strongly shape the outcome.