When it comes to memorizing new information, learners that take active control of the process do a better job. At least that is the finding from research at the University of Illinois recently reported in Nature Neuroscience.

When it comes to memorizing new information, learners that take active control of the process do a better job. At least that is the finding from research at the University of Illinois recently reported in Nature Neuroscience.

Subjects were asked to memorize the location of specific objects found at different points in a window on a computer screen.

“The “active” study subjects used a computer mouse to guide the window to view the objects. They could inspect whatever they wanted, however they wanted, in whatever order for however much time they wanted, and they were just told to memorize everything on the screen,” Voss said. The “passive” learners viewed a replay of the window movements recorded in a previous trial by an active subject.”

The active learner significantly outperformed the passive learner. Brain scans revealed that the hippocampus plays a more significant role during active learning and is likely responsible for improved memory performance.

From a cognitive design perspective, having control means increased mental work or effort. The subject makes more decisions and exercises more self direction. There is likely more emotional uncertainty to manage. Fortunately, this increased mental effort is translated into a better learning outcome. Less task structure more deeply engages the brain in learning.

This should be no surprise to many educators that already promote active learning. What is interesting though is the specific definition of what constitutes the cognition behind “being active”. In this case control over the stimulus environment engages the hippocampus. This likely makes (and I am speculating) memorizing something secondary or incidental to a more natural whole-brain activity.

This should be no surprise to many educators that already promote active learning. What is interesting though is the specific definition of what constitutes the cognition behind “being active”. In this case control over the stimulus environment engages the hippocampus. This likely makes (and I am speculating) memorizing something secondary or incidental to a more natural whole-brain activity.

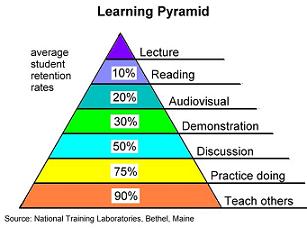

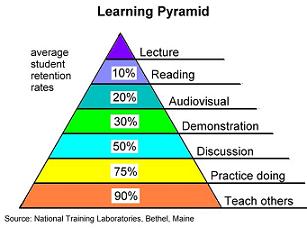

Deep and lasting learning happens automatically as we engage our brains in problem solving, planning and other activities of daily life. The learning process becomes problematic when we make it our primary focus or de-contextualize it and engage in formal learning in a classroom. Active learning changes our cognitive priorities and gets other brain regions involved and produces better outcomes. As we move to the base of learning pyramid (shown above) we are engaging student’s in “designed experiences” rather than formal learning exercises and retention increases dramatically.

Reading, lectures and other devices of formal learning are still important, especially as they set up the designed experiences of learning or to help debrief them. If we want to optimize educational processes for how student’s minds actually work we must design and deliver experiences not lessons.

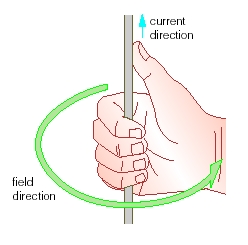

New psychological research shows that encouraging the use of hand gestures improves spatial visualization. When trying to mentally manipulate an object, using hands to “see” the shape and behavior of the object improves our ability to make judgments and learn.

New psychological research shows that encouraging the use of hand gestures improves spatial visualization. When trying to mentally manipulate an object, using hands to “see” the shape and behavior of the object improves our ability to make judgments and learn.

This should be no surprise to many educators that already promote active learning. What is interesting though is the specific definition of what constitutes the cognition behind “being active”. In this case control over the stimulus environment engages the hippocampus. This likely makes (and I am speculating) memorizing something secondary or incidental to a more natural whole-brain activity.

This should be no surprise to many educators that already promote active learning. What is interesting though is the specific definition of what constitutes the cognition behind “being active”. In this case control over the stimulus environment engages the hippocampus. This likely makes (and I am speculating) memorizing something secondary or incidental to a more natural whole-brain activity.