In nearly every talk I give on cognitive design someone asks about designing for trust. This includes offerings to create and maintain the trust of customers as well as management practices to create and maintain trust with employees.

This is a great design question to ask because trust is a complex cognitive relationship we establish over time with people and a wide variety of artifacts. My answer takes the form of a simple recipe:

A. Be sure to include the 7 features of trustworthy products in a way that customers feel

B. Give products and services a trusting “personality” when possible

C. Establish a service recovery process that restores the customer’s perception of justice

Research shows I tend to trust products/services that are:

-

* Reliable (perform in a predicable way across circumstances)

-

* Transparent or easy to understand

-

* Under my control (options, personalization, easy termination)

-

* Secure and safe (won’t hurt me or let me hurt myself)

-

* Insures my privacy (to the degree I want it)

-

* Have guarantees (a form of promised service recovery)

-

* Are self maintaining or automatically serviced by the provider

On the surface, most of these features seem to be a matter of engineering and usability. But how I establish the cognition (feeling) for each of these factors is key and very much depends on the industry context. For example, years ago Progressive Insurance started offering a free and easy to use quoting service that shared the cost of their policies and the cost of their competitor’s policies even when Progressive’s policies were more expensive. This was a bold move in establishing the cognition of trust in an industry that has had low levels of consumer trust. It clearly telegraphed – we are not trying to hide our prices (transparency) – and gave consumers a level of control and understanding that was otherwise hard to obtain. They establish a mutual interest with consumers – understanding the comparative price of policies even to their potential detriment. If we have a mutual interest, and you show a reasoned willingness to go may way on occasion, I can trust you.

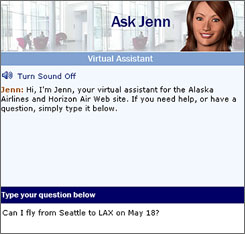

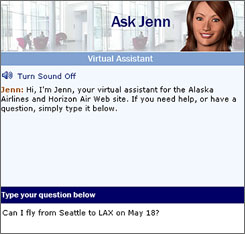

Products with personality or those that have features that cause me attribute human-like qualities to them may play a special role in creating and maintain trust. There is some data that suggest people see simple geometrically styled products as “sensible and trustworthy”. Other more personified products that talk to us (cars) or are stylized after living or imaginary characters (e.g. cartoon characters) may in fact invoke cognitions that lead to higher levels of trust (my speculation). The development of avartars or 2-dimensional representations of personalities for customer service (an animated figure that moves, gestures and speaks with you) over the web is one experiment along these lines. Well designed service avatars run on a touch of artificial intelligence and do well at understanding natural language. Check out the article about Jenn a service Avatar for Alaska Airlines.

We can now develop customized avatars (and buddy icons) to express dimensions of our own personality for many online interactions (email, instant messaging, social networking, games, etc.). This is powerful cognitive design medicine. After all, if I can’t trust myself (even as an avatar) who can I trust?

Cognitive design for trust is really put to the test during service recovery. When a product or service fails, consumer expectations and trust are betrayed. How I recover form this betrayal strongly determines how much I should be trusted in the future (assuming the breach is not consistent or acute) Organizations seek to recover that trust by “making things right again” through a service recovery process. Some researchers argue that service recovery is mediated by emotions. According to the appraisal theory of emotions – emotional states are generated when we assess (or appraise) a situation’s fit with our goals, beliefs and values. Clearly, in the case of a service failure the essence of the situation is a negative appraisal and attending emotional states. But how can we characterize these emotions in a way that helps us design a better service recovery process?

An interesting a recent answer to this question is that we can characterize the design problem in terms of restoring “perceived justice”. According to Chi Kin (Bennett) Yim and co-authors, consumers want three types of percieved justice in a service recovery process: procedural (a compliant process that is easy to access, fast and transparent), interactional (treated with fairness, empathy, courtesy during the process) and distributional (compensated for the service failure). The study suggested that positive outcomes in service recovery (e.g. continued customer loyalty) were mostly driven by distributional justice or the compensation given because of the failure. From a cognitive design perspective this is not surprising as it demonstrates that the organization is “putting its money where its mouth is”.

Being nice to me is one thing (and expected) but showing that you are willing to give me something that reflects a shared value is a big step in re-establishing trust.

Working out a calculus for distributional justice is no easy matter. Over compensation during service recovery can lead to consumer guilt, under compensation can lead to anger. Time-to-compensation and who delivers it (e.g. high ranking official or the clerk that made me mad) may also be important variables. The corporate mindset may also impose the ideas that all customers must be treated identically during service recovery.

The art of cognitive design for service recovery is found in the specifics of the what-and-how customers are compensated for a failure. It need not be complex – Domino’s Pizza is delivered in 30 minutes or it is free.

Blunders in service recovery may lead to serious customer defection (although I have found no research to support that). Service recovery is like a second chance it the relationship. You mess that up and how can I trust you?